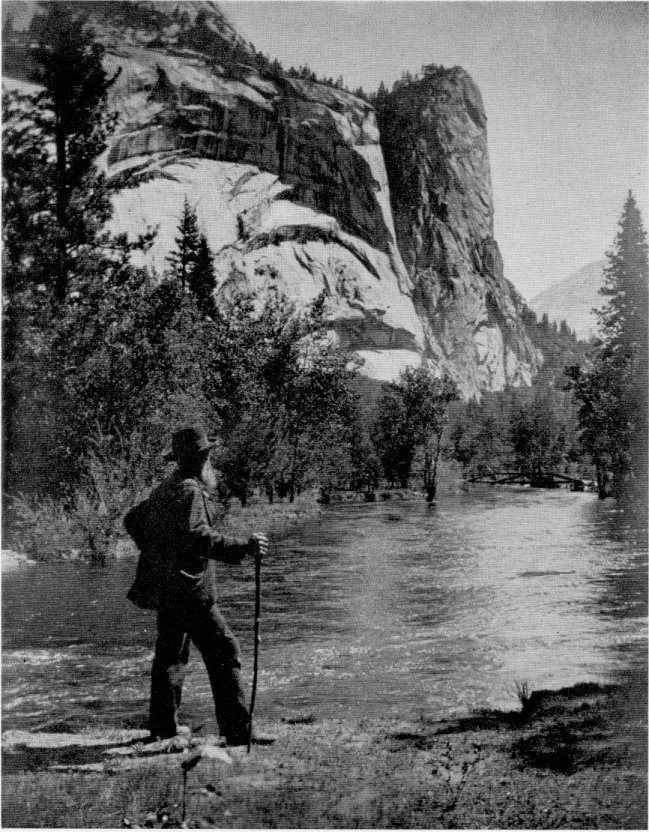

As someone interested in history,

in the environment, in wilderness, conservation, and writing, I am ashamed to

say that I just learned about John Muir, the late 19th century

Scottish- American naturalist, last month. From a comic. Muir is famed for

petitioning the U.S government for the creation of Yosemite national park, and

also for his involvement in the Sierra club and other moves for conserving

wilderness in the U.S. I decided to read the only of Muir’s books my library

had on offer, My First Summer in the

Sierra, to dip into oldey-timey conservation and naturalist writing, hoping

to find connections and optimism for movements today.

It is hard

not to feel deeply for the environment as Muir sees it; he admires all life,

even the ferocious bears and irritating Douglas squirrel, and laments the very

undergrowth that the flock of sheep he accompanies lays waste in its trampling

past. It is no surprise then, that he feels deeply the wound capitalism has

created between man and the ever-connected and brotherly web of nature he sees

before him. This occurs mainly in his observations of Shepherds in California,

whom are degraded and exhausted by their economic strife, and may only be

driven by hopes of escalating in the capitalist system by saving up to buy a

flock of their own. I can think of no better summarizing image than the one

Muir paints of Billy, the shepherd he accompanies, who’s clothing becomes

entirely coated over time with the greasy, fatty dripping of the lunch he ties

to his belt, meaning that “instead of wearing thin [his trousers] wear thick.”

Billy has no emotional connection to the sheep, remarking often when one goes

astray that he is not paid enough to keep saving them.

It is thus

greatly surprising, considering Muir’s deep-felt empathy for nature and his

lamentations about the Arcadian shepherd being broken by American capitalism,

to read his shocks and spites for Native Americans, in this era still referred

to widely as ‘Indians.’ From the off Muir writes of the feeble and weak ‘Digger

Indians,’ who are never specified by tribe, culture or nation, instead just a

taxonomic ugliness akin to the South African settler’s naming of the ‘bushman.’

Muir frequently writes of the Indians sustenance on nature, of which he is

jealous of as he and his colleagues must rely on deliveries of bread and other

supplies which runs dry for an uncomfortable time. He also writes of their

skill in living in their environment, as he is startled a few times by the

sudden and silent appearance of a Native in their camp. Despite these

admirations, he still affords them little acknowledgement for their

ingenuities. He remarks on their ragged clothing, their begging for whiskey or

tobacco, without really acknowledging the corrupting effect of white capitalist

invasion in the same way he affords the white shepherd.

I am sure

there are a number of ways to understand his perception of native Americans,

but I find it most hard to digest as a result of his perceived special ‘Scotchness,’

which I feel Muir stresses to tie him stronger to nature within the capitalist

systematics of shepherding in California. When commenting on the Californian

shepherds ill education, grimy food and overall depressing life, he compares it

to the Scottish shepherd, whom he praises alongside the ‘Oriental shepherd’ for

maintaining a keen intellect and interest in culture. Muir also retells an

event where, in the dead of night, he ‘felt’ that a friend of his was nearby,

and in the morning found that his friend was indeed in the valley he felt him to be in, to everyone’s surprise. This is

written as being an event of extraordinary ‘Scotch farsightedness.’ I

want to believe that, as result of his belief in himself as Scottish and thus

different in culture etc. to other Europeans, Muir would understand other

cultural uniquenesses and admire them in the same way he would admire a

forested valley. I am no great scholar of Muir, but I feel that, between his

heightened Scottishness and his flippancy towards the fascinating lives

of Indians who understand and admire their environments as much as, if not

more, than muir, exists the kind of Celtic, white-supremacist mythologizing

that helped spawn various blights to the development of American culture(s)

such as the Southern confederacy, which borrowed the very flag design of Scotland for their own, and also the Ku Klux Klan, who borrowed the symbolism of the 'clan' for their own twisted ends. Like I said, I am not great

scholar of Muir, and also never knew him personally, but on closer critical

reading I have dug up this dull residue of his understanding of the Natives of

the wild lands he so greatly admires.

I have

written the above without even dipping into his mentionings of ‘Chinamen,’ some

vague myths he recounts of Indian surrenders, and also an event in passing that

was of interest to me, wherein he claims to have enjoyed the company of a

general of the Florida Seminole wars, one of many wars between white invader

and Native Americans.

(The comic that I mentioned is this one: http://noahvansciver.tumblr.com/post/159136532289/a-sequence-on-john-muir-from-my-upcoming-book )